The Stone of Destiny has two enduring characteristics. One is to galvanise the nation of Scotland and the other is to twist the knickers of the British establishment. Last week, that celebrated lump of sandstone has demonstrated its power yet again

(Alex Salmond cited in The Daily Record, 7 January 2024)

Scottish nationalist Salmond’s assertion stemmed from the disruptive agency of just a fragment of the Stone (above image (c) Scottish National Party). This story returned to the media yesterday, just as I was finalising this blog, with publication of the the Scottish National Party (SNP) intention to pass the fragment in their possession to the Commissioners for the Safeguarding of the Regalia (background below). As reported in Alastair McNeill’s article in the Daily Record for 27 March, the SNP express the desire that it is passed to the new Perth Museum. This opens to the public on 30 March with the Stone of Scone as its centrepiece.

Beginning my research in 2020, I had not appreciated just how many fragments of the Stone exist or are known to have existed. Not featuring in previous academic studies, they are central to mine. And the joy is that they keep emerging, in all senses. This blog explains the fragmentation of the Stone and introduces these fragments. It would be lovely to flush out some more examples!

As a monument, the Stone began its life as a fragment of the earth’s geology. It was quarried at an unknown time from very close to Scone. This fragment became a ‘whole’ object in its own right.

Reworking of the Stone through time then led to its fragmentation. Block-like, its six surfaces have been worked at many times in its life. The full sequence of events, their dating and what they represent is difficult to establish (Hill 2003; 2016). Metal tools in the hands of unknown people have resulted in the loss of outer surfaces. The most obvious example is the sinkings made to allow the iron rings that were attached to the sides of the Stone to lie flat within its body, or the rectangular groove cut into the top surface. Fairly large pieces have been somehow knocked off the arrises of the Stone, deliberately or otherwise (Rodwell 2013, 173-74). We have no evidence that any fragments were deliberately taken to be kept, until modern times that is.

Two contexts generated tiny fragments that have been ‘curated’, formally and informally: specimens collected for scientific analysis in the nineteenth century; and fragments collected by people with access to the Stone in 1951, before it was returned to Westminster Abbey. To remind you, the Stone has broken into two large fragments, along a historic crack, when Glasgow students pulled it from the Coronation Chair onto the floor of Westminster Abbey on Christmas Eve 1950. A Glasgow stonemason repaired the Stone in March 1951.

Scientific specimens

As a British Geological Survey (BGS) blog reminded us around the May 2023 Coronation, there is a group of tiny specks or fragments of the Stone collected by geologists. Originally stored in London, these were transferred to the Scottish Rock and Mineral collection of the BGS in Edinburgh, where all but one sample now remains. Rachel Cartwright and Emrys Phillips of the BGS have kindly helped me to make sense of their multiple sources.

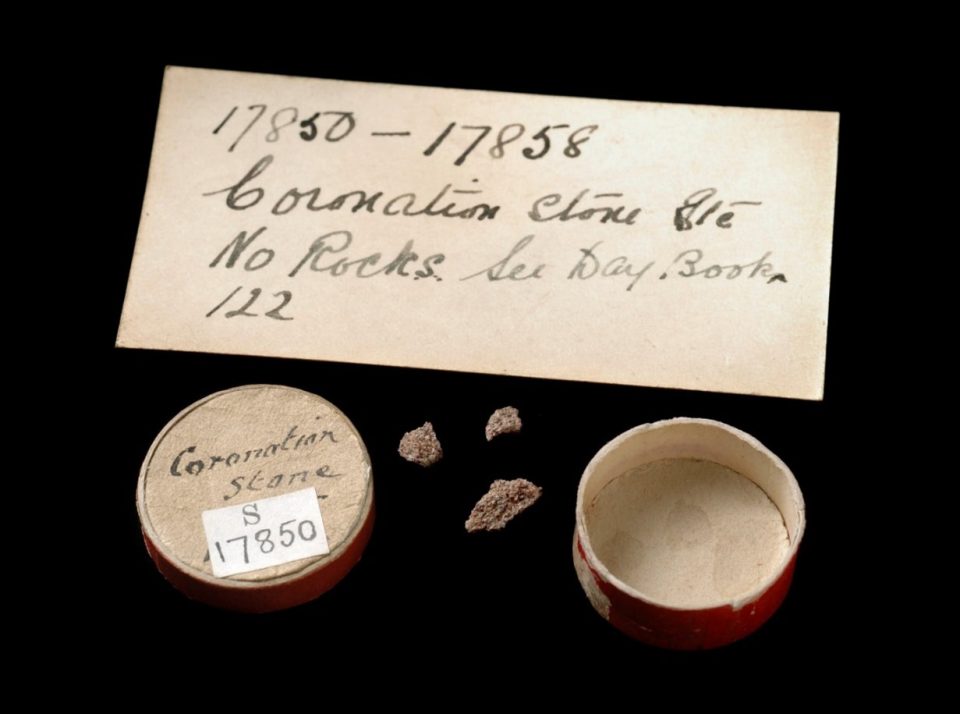

In the late nineteenth century, several samples were removed from somewhere on the Stone for the purpose of geological analysis. The Dean of Westminster, Arthur Penryn Stanley, described organising a party in 1865, including eminent geologist Sir Andrew C Ramsay, to examine the Stone. Ramsay took sweepings from the Stone – as many grains as might cover a sixpence (Stanley 1868, 499-501). Sir Jethro H Teall accessioned them as part of the BGS collection in 1892. The apparent context is that in 1892 the Stone had been cleaned, so Teall also collected and accessioned four ‘loose rock chips’, ‘minute fragments’ (Davidson 1938, 210). These are what the BGS register refers to as ‘crumbs from the Stone of Scone’, about 10-16mm in width (Fortey et al. 1998, 148). Two of Teall’s chips have recently had new lives.

BGS samples S17850 to S17858 – ‘crumbs from the Stone of Scone’.

Photo: British Geological Survey image © UKRI All rights reserved (permit no. CP24/008)

New life as a modern scientific sample

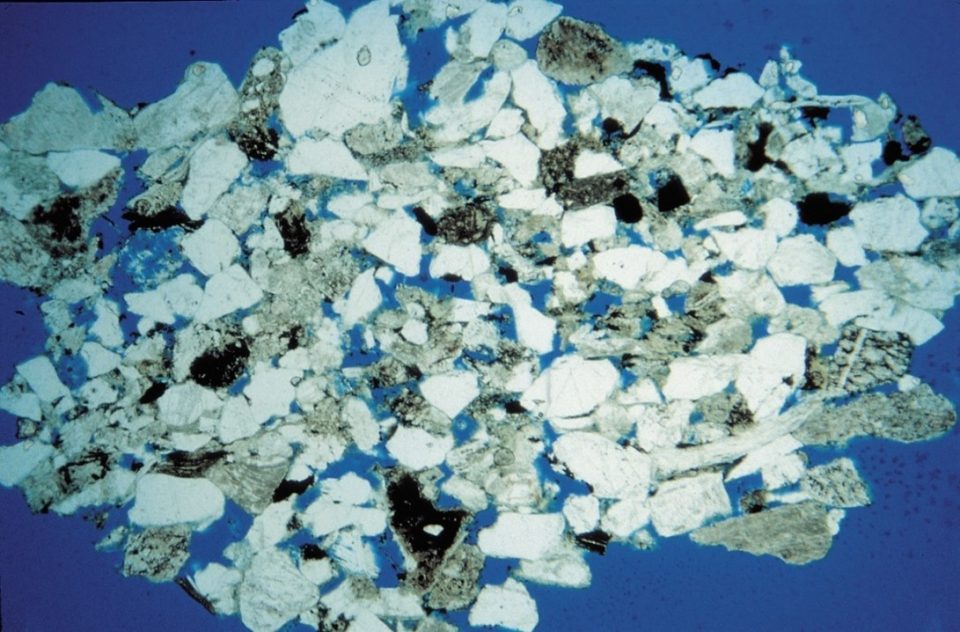

One of the BGS fragments was ‘consumed’ after preparation ‘with great care’ to make a thin section in 1996. Not to beat about the bush, this means it was partly destroyed but to create a sample fit for modern geological analysis. Importantly, this enabled the BGS to add more precision to the geological origin of the Stone (Fortey et al. 1998; Phillips et al. 2003). In reality, and indeed in BGS formal accessioning terms, this fragment became a fragment (subset) of itself.

Geological sample of the Stone at x2.5 magnification under plan polarised light.

Photo: British Geological Survey image P054628 © UKRI All rights reserved (permit no. CP24/008)

New life and home in a ritual context

The fate of a second BGS chip is something that I first thought must be an online factoid. Luckily, I checked. A part of the Stone has been to Australia and back, and is built into a royal coach!

One of the BGS samples is mounted behind a circular glass window (think tiny porthole), immediately beneath the centre of the two front-facing seats in the Diamond Jubilee State Coach.

Photo: Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024. Thank you to the Royal Collection Trust for producing this new photography.

The new king and queen sat in this comfortable new Diamond Jubilee State Coach, the fragment of the Stone between their legs, as they journeyed to Westminster Abbey for their Coronation on 6 May 2023.

Photo: Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024.

For their journey, the king and queen were in fact surrounded by a time capsule of fragments representing:

the most intense collection of the great events, figures and objects of British history ever assembled, items directly related to the most influential events and characters in British history, her greatest victories, her most treasured places, and her greatest contributions to the world (see here).

Other Scottish contributions were pieces of timber from Edinburgh and Stirling Castles.

The Australian maker of the royal carriage, Jim Frecklington, used to work in the Royal Mews at Buckingham Palace. On Australian television, he described the Stone as ‘probably one of the most important items’ (Today Show Australia, 6 May 2023). ‘We could not have hoped to dream that a small piece of the Stone of Scone could be made available through the kindness and vision of the Government of Scotland’, he said (see Acknowledgement here, link located from here). So how did this intriguing story come about?

The relevant records of the Commissioners for the Safeguarding of the Regalia are not yet publicly accessible in the National Records of Scotland. For the back story, as I currently have it, I am grateful to the following for information: Historic Environment Scotland per Kathy Richmond, former First Minister, Lord McConnell of Glencorrosdale, Karen Lawson and Sally Goodsir at the Royal Collection Trust, James Hynd, Director and Secretary of Commissions, Scottish Government, Terri Thomson of the Scottish Government Protocol & Honours Team, and the BGS as above.

Frecklington’s manufacture of the coach begun in 2004 but was not completed until 2013, when it was donated to commemorate the 60th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s succession. It was a private initiative – clearly a labour of love – but supported with a small grant from the Australian government and other donors (see story about its manufacture here, but note that this article and other sources incorrectly identify the Stone fragment as stemming from the 1950/51 breakage of the Stone).

In around 2007, Frecklington had approached HES’s predecessor body, on behalf the Australian Government, for a piece of the Stone. Historic Scotland declined – it would have required breaking off a new fragment, after all. Instead, Frecklington approached the BGS. The Senior Managers of the BGS and its Collections Advisory Panel agreed to donate one of their samples (see above) but state that they first sought and obtained the permission of the Right Honourable Jack McConnell, in his capacity as one of the Commissioners for the Safeguarding of the Regalia. That’s a responsibility that goes with being First Minister of Scotland. Neither the Commissioners for the Safeguarding of the Regalia nor HES have been able to find any sources related to this request, and Lord McConnell also tells me he does not remember it. But the outcome is that the fragment is now safe in the care of the royal family.

Trio of souvenirs from the Stone’s heart

Hidden in plain sight since at least 1980, mentioned in various media, particularly around the 1996 return of the Stone, are fragments of the Stone kept by the Glasgow students who took the Stone in 1950.

In 1980, Kay Matheson, the only female conspirator, told the Daily Record (22 December 1980), ‘I have a tiny piece of the Stone in a locket round my neck to remind me of those days’.

Photo: (c) Reach Publishing Services Ltd

Matheson’s grave in Poolewe kirkyard, near Gairloch (Highland) speaks to her reclaiming the Stone and attracts nationalist-themed offerings. It is enormously tempting to speculate that she might have been buried with that locket and its precious fragment (see later example), unless a relative or friend has inherited it.

Photo: Sally Foster

Speaking to Alastair Dalton of the Scotsman (4 July 1996), Sheila Hamilton, the former wife of lead conspirator Ian Hamilton, revealed that ‘three pieces of the stone, each just larger than a 50p, were mounted as jewellery’ and were ‘thought to have gone to fellow conspirators’ (see Matheson’s locket above). Ian Hamilton had his later wife’s fragment enshrined in a silver brooch with a symbolic if relatively modest design, as would have befitted his means at the time. A circular band of silver with applied ‘Celtic’ symbols (a birlinn, ring-headed cross and interlaced animals) clasps a rhomboidal fragment of little more than 40 mm maximum width. Ian gave it to Sheila as a 21st-birthday present on 8 July 1951, ‘with best wishes for the years of wisdom’. On the back, the Stone’s traditional prophecy is inscribed:

Unless the fates should faithless prove and prophets voice be vain, where’er this sacred stone is found the Scottish race shall reign.

Elisabeth Niklasson of the University of Aberdeen and I thank Ian and Sheila’s son, Jamie, for bringing his mother’s brooch to our project workshop held at the University of Stirling. Jamie and the family brooch story will feature in a forthcoming Marc Fennell’s podcast for his series 2 Stuff the British Stole.

Photo: Sally Foster

Who owns the third fragment made into jewellery, and its current fate, are not known. Perhaps it went to a girlfriend of Gavin Vernon or Alan Stuart, the other students who took the Stone from Westminster Abbey.

As Sheila Hamilton hints in her interview with Dalton – the Stone ’was repaired with all but the fragments by a Glasgow stonemason’ – the vector for the acquisition of all these fragments was Bertie Gray, the Glasgow stonemason whose head mason prepared the fragmented Stone before it was symbolically left on the high altar of Arbroath Abbey, on 11 April 1951.

It is fair to assume that conjoining the Stone’s two cracked faces was a messy affair. Likely there were loose bits of stone. Certainly, the Stone was drilled / cored to insert three metal rods that have since conjoined the heavy fragments. These industrial sutures are only visible in X-rays, unknown to most visitors to the Stone. The gap between the two fragments was sealed with cementitious fill; Historic Scotland toned down the colour of this highly visible modern mend when the Stone came into its care in 1996, but it is readily visible in the excellent display and lighting of the Stone in Perth Museum.

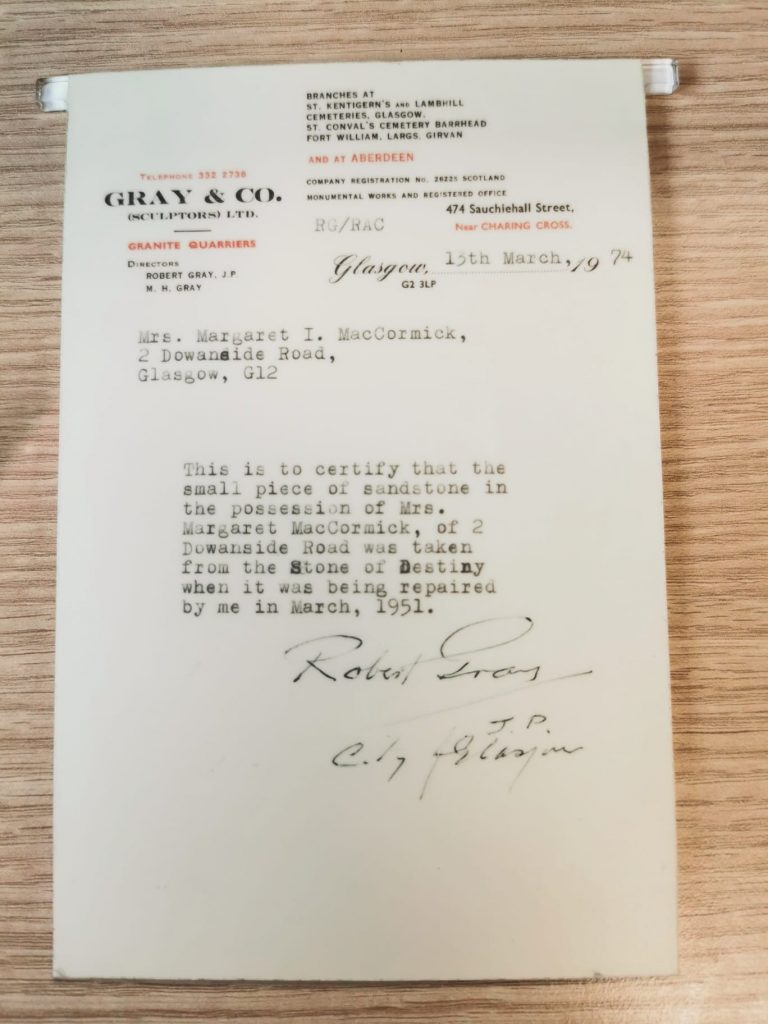

Certified fragments of the Stone

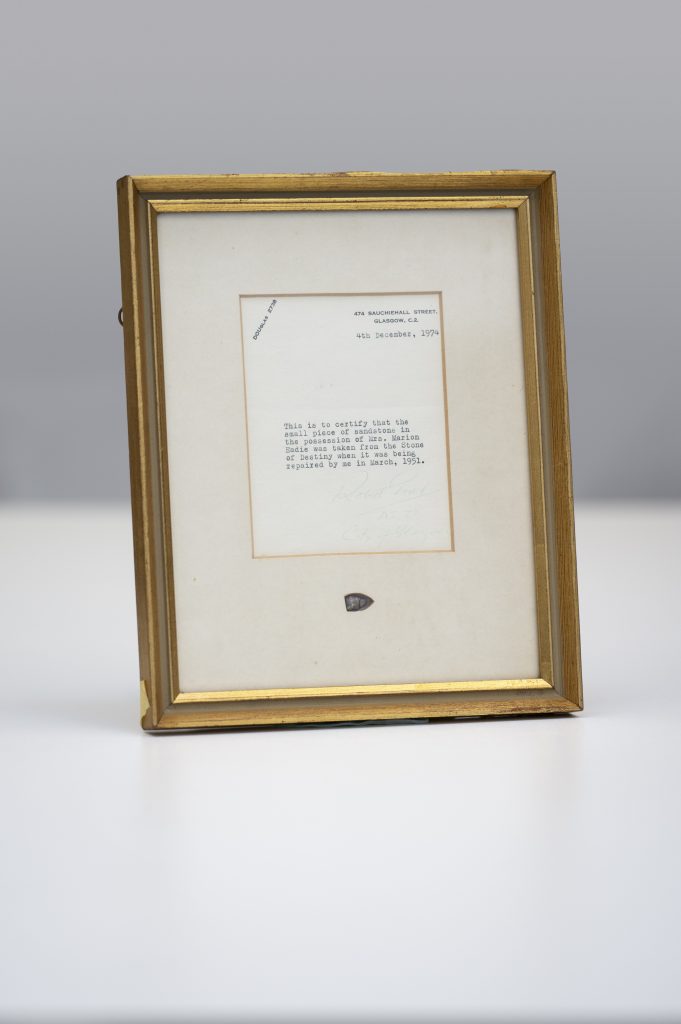

Robert (Bertie) Gray was also a local politician with strong nationalist sentiments. He is credited with having made two copies of the Stone in 1929, not long after being involved in setting up the National Party of Scotland in 1928, which later merged to form the SNP in 1934. His replicas are most likely to be the examples now in the Arlington Bar in Glasgow and the one held somewhere in secret by the Knights Templar. Gray must have kept a stash of fragments of the Stone, for on two occasions in 1974, during the last 13 months of his life, he gifted an piece with an accompanying hand-signed letter to validate its material authenticity.

In 2018, Gray’s daughter put her framed letter and fragment up for sale at Lyon and Turnbull’s, where it was expected to reach around £3000 (The Courier, 1 August 2018):

This is to certify that the small piece of sandstone in the possession of Mrs. Marion Eadie was taken from the Stone of Destiny when it was being repaired by me in March, 1951.

Photo: (c) Historic Environment Scotland. Thank you to HES for arranging this new photography.

Concern about the sale of part of the Stone led to the item’s discreet withdrawal from auction. The case was put forward to the Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel (SAFAP) for Treasure Trove allocation. This raised some difficult questions about ownership and reward responsibility, but the QLTR (Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer, as it was then) and SAFAP ultimately agreed its allocation to HES with an acquisition price of £6500 (SAFAP minutes 5 December 2018, reference TT128/18). It is not yet known if and how this assemblage will be displayed in the future, and where. The Stone itself was formerly on display in the Crown Room of Edinburgh Castle, in a sturdy glass case, alongside the Honours of Scotland (royal regalia).

The other letter, on Gray & Co. headed notepaper, says:

This is to certify that the small piece of sandstone in the possession of Mrs. Margaret MacCormick, of 2 Dowanside Road was taken from the Stone of Destiny when it was being repaired by me in March, 1951.

Photo: (c) Scottish National Party. Thank you to Ross Colquhoun for the photography.

This gift is the now-infamous fragment that made media headlines (see picture below). Its existence was bandied about on the floor of the House of Commons in January 2023 (see previous blog). Experts at HES were being consulted on its material authenticity (see, for example, Daily Record, 27 March 2024), but this is hardly in doubt given this letter and the pattern of Gray’s gifts.

This is the fragment of the Stone of Destiny (or Scone), as it was displayed in the Scottish National Party headquarters. (c) Scottish National Party.

The attention and controversy began with the publication of the Scottish Cabinet Papers for 16 September 2008 (NRS SCR14/71/63):

38. The First Minister said that he had met with Professor Sir Neil MacCormick, who had presented him with a fragment of the Stone of Destiny as a personal gift. The Permanent Secretary agreed that the fragment need not be surrendered to Historic Scotland.

Mrs MacCormick was the wife of John MacCormick, a Scottish nationalist politician. In 1950 he was Rector of Glasgow University when he offered practical support to the students to take the Stone. I discovered this family fragment while reviewing Stone-related sources in the University of Stirling Scottish Political Archive. ‘I remember this little bit of stone in a box my mother always kept and told me it was part of it’, said Iain MacCormick, son of John, talking to Billy Kay in 2011 (SPA/OH/BK/2). Marion MacCormick added, ‘she was terribly proud of it, she used to keep it in the bookcase, do you remember, in between two books. She was always showing this. Neil and I … we bequeathed this Stone, the little bit, to the Scottish Nats HQ and that’s where it is just now’ (SPA/OH/BK/2). I followed this up with SNP HQ on 21 September 2023; they very kindly and promptly sent over photos of both the chip and Gray’s letter of authentication.

Who else in the wider circle of people associated with the secret events of 1950/51 did Gray decide to give a piece of his, as well as the nation’s, history? Since I first published this blog, I have learnt that a lady with such connections who lived in Cambusbarron, near Stirling, wore a fragment of the Stone in a necklace (pers comm. Ken Lawton). It also transpires that Gray distributed fragments more widely, making sure that a fragment ended up in Australia, of which more to follow in due course.

Since this blog was first published on 28 March, there was also a development on 17 May. On behalf of the Commissioners for the Safeguarding of the Regalia, Scottish Government published HES’ geological analysis, concluding after also taking into account provenance (see above) that ‘there is a high degree of certainty’ that the fragment comes from the Stone. The fragment is being retained by the Commissioners ‘on behalf of the Nation and people of Scotland. The Commissioners will now consider appropriate options for the future location of the fragment, including the option of it being placed in the new Perth Museum’. Both the current and previous First Minister recused themselves from the decision-making process, given the obvious conflict of interest as SNP members.

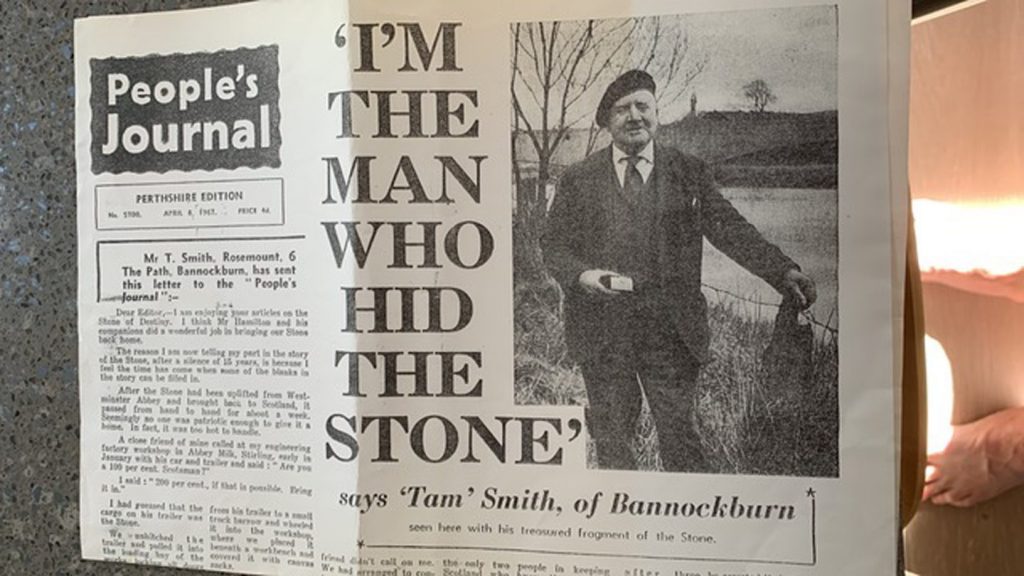

The ‘Stirling’ fragment

Whoever would have guessed, but a further fragment of the Stone was created by chiselling off a small part of the large fragment of Stone, we can assume its broken surface, just miles from where I am writing. It is almost certainly buried here (in Bannockburn Cemetery). The interest generated by the ‘Alex Salmond’ fragment, led to a fascinating article by Neil Drysdale (Press and Journal, 13 January 2024) after he was contacted by his friend Dr Ken Lawton.

On its arrival in Scotland in January 1950, the Stone needed a safe home. We learn that Tam Smith from Bannockburn was asked by a ‘friend’ (must be Bertie Gray) to look after something that he realised was the Stone. Smith looked after this portion of the Stone for around three months in his Stirling Abbey Mills light-engineering workshop, before it was taken to Glasgow to be reunited with the smaller portion, repaired, and left on the high altar at Arbroath Abbey.

Photo: (c) Ken Lawton, with permission.

His grandson Ken Lawton told Neil Drysdale about Tam’s pride:

He was a true nationalist and was quite happy to play a role in keeping the stone hidden from the authorities. In his terms, the stone hadn’t been stolen, but brought back to where it belonged in the first place, and he even took a little bit of the artefact which he kept in a matchbox in a secret drawer and which he would show a few of us at family gatherings … although he wasn’t part of the plot, he was proud to be a link in the chain … He was also thrilled he had a small fragment of the stone in his possession from when he was guardian and I’m sure it was buried with him in Bannockburn Cemetery.

I interviewed Ken Lawton on 25 July 2024 and will be able to amplify this story further in my planned publication on the Stone fragments.

My next steps

If you are familiar with my existing research on replicas and its implications, you will appreciate why I argue that researching the individual and composite biographies of the Stone and fragments is critical to establishing the contemporary meanings, values and significance of the Stone. At the same time, the fragments each contribute their own (interlinked) lives, meanings and values. In practice, the Stone is a distributed thing with composite and diverse new lives, and I find this historical outcome a very positive rather than a negative matter, and I am not alone.

I mean, they’re just charged with such meaning […] really powerful stories. […] What I would want most of all is that there is a sense that this story is joined, properly joined up.

[…] there are bits of Stone out there, carrying the story, telling…telling other bits of the story in a rather lively way. So, I think that’s what I’m arguing for really, for us to have the best and fullest history we can, but it’s awkward, and it’s a bit contested and […] you need to be aware of those different viewpoints.

(The Very Reverend Dr David Hoyle, Dean of Westminster, in interview with me on 8 April 2024, when in the context of a wider interview, one of my last for this project, I used the opportunity to ask him about the many fragments that we are learning exist of the Stone)

Photo: Sally Foster

I will be continuing to research the fragments and to consider them from a critical heritage perspective, leading to a journal article, with questions including:

- In what ways can these fragments’ lives be best appreciated in their own right and as part of the evolving life history of the Stone. What do the fragments themselves do, individually and corporately?

- In understanding the meanings and values of the fragments, what part does their movement play?

- To whom do the fragments matter, what, how and why? This embraces the matters of identity, sense of belonging and legal ownership.

- How, if at all, does their materiality shape the way that the fragments carry meaning and they are valued?

- What happens when a fragment physically becomes part of or is related to a specifically created object (not forgetting how the Coronation Chair was created as a reliquary to hold the Stone, which it did for nearly 700 years)?

- How important are these fragments in the overall story of the Stone?

- Is the Stone diminished or enhanced by the existence of these fragments?

- How does legal ownership or location of the fragments affect the stories they tell or could potentially tell? For example, do we want to collect all the fragments of the Stone together or display and tell their stories in different places? Fragments can be readily circulated, unlike a Stone that weighs 152 kg.

See here for academic published sources that have been cited above.

Blog updated 30 April 2024 with further images from the BGS and quote from interview with the Dean of Westminster. Blog further updated 17 May 2024 with publication of Scottish Government news on the fragment that had come into the care of the SNP, and an update on sources for what happened in 2007. Further updated 26 July 2024 after interview with Ken Lawton and new information from Queensland Museum, Australia.

Queries or further information: Professor Sally Foster. Full project website: https:\\thestone.stir.ac.uk.